IDRC - Celebrating 25 Years

1993 - 2018

Continuing Our Work During COVID-19

Read the letter regarding COVID-19 by IDRC Director, Jutta Treviranus.

Supports for complying with the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA)

How do I make my web site accessible? How do I make my office documents accessible? How do I make information available in alternative formats? Businesses and organizations read our AODA Help.

Dana Ayotte

Designer

205 Richmond St., 2nd floor

Toronto, ON

M5V 1V3

Phone: 416-977-6000 ext 3959

What is Inclusive Design

What do we mean by Inclusive Design?

We have defined Inclusive Design as: design that considers the full range of human diversity with respect to ability, language, culture, gender, age and other forms of human difference.

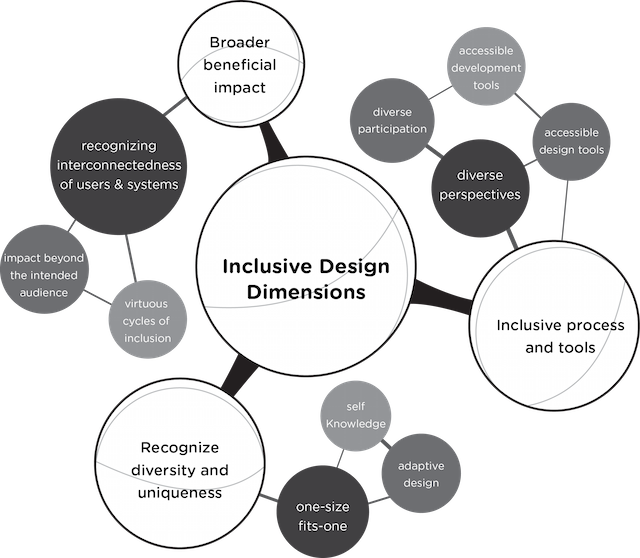

The Three Dimensions of Inclusive Design

At the IDRC and the Inclusive Design Institute we stress three dimensions of inclusive design:

1: Recognize diversity and uniqueness

Inclusive design keeps the diversity and uniqueness of each individual in mind. As individuals spread out from the hypothetical average, the needs of individuals that are outliers, or at the margins, become ever more diverse. Most individuals stray from the average in some facet of their needs or goals. This means that a mass solution does not work well. Optimal inclusive design is best achieved through one-size-fit-one configurations. Flexible or adaptable systems such as digital systems are most amenable to this but the emergence of 3D printers and other mechanisms of bespoke manufacturing and component-based architectures can also achieve diversity-supportive design. This does not imply a separate, specialized or segregated solution. Segregated solutions are not sustainable economically or technically. Inclusively designed personalization and flexible configurations must be integrated to maintain interoperability and currency. This also does not imply adaptive systems that make choices for the user. Inclusive design recognizes the importance of self-determination and self-knowledge. Design choices or configuration choices vest with the user and the adaptive design fosters the growth of self-knowledge wherever possible.

2: Inclusive process and tools

The process of design and the tools used in design are inclusive. (This dimension is in line with Scott Page’s observations regarding the performance of groups that include diverse perspectives. Scott Page has empirically shown that a group that includes diverse perspectives, especially perspectives from the margins, trumps a group of the “best and brightest,” in decision-making, accurate prediction and innovation). Inclusive design teams should be as diverse as possible and include individuals who have a lived experience of the “extreme users” (as coined by Rich Donovan) the designs are intended for. This also respects the edict “nothing about us without us” without relegating people with disabilities to the role of subjects of research or token participants in design exercises. To support diverse participation and enable the design to be as closely linked as possible to the application, the design and development tools should become as accessible and usable as possible. This dimension does not denigrate the skills of professional designers but calls for those skills to become more accessible and for the design process to become more inclusive of diverse designers and consumers.

3: Broader beneficial impact

It is the responsibility of inclusive designers to be aware of the context and broader impact of any design and strive to effect a beneficial impact beyond the intended beneficiary of the design. Inclusive design should trigger a virtuous cycle of inclusion, leverage the “curb-cut effect”, and recognize the interconnectedness of users and systems. To realize this broader positive impact requires the integration of inclusive design into design in general. This third dimension supports the healthier, wealthier and wiser societies Wilkinson and Pickett observed in their research of more equal communities.

The Relative Nature of Disability and Accessibility

The IDRC reframes disability within the design context. Rather than a personal characteristic or a binary state (disabled vs. non-disabled), disability is framed as: a mismatch between the needs of the individual and the design of the product, system or service. With this framing, disability can be experienced by anyone excluded by the design. For example, when listening to an audio-only lecture the student who is blind is less disabled than the student who has not read the background material, the student who is less fluent with the language, or the student who has been up all night. An audio lecture is designed for a student who has the contextual knowledge, understands the language well, and can fully attend. With this framing anyone can potentially benefit from inclusive design.

Accessibility is therefore the ability of the design or system to match the requirements of the individual. It is not possible to determine whether something is accessible unless you know the user, the context and the goal.

Why not use the term Universal Design?

Inclusive Design, as we use it, can be seen as Universal Design with a number of provisos.

When we chose the term we wanted to distinguish it from the then current associations with the term Universal Design. The associations that we want to avoid are not necessarily part of any formalized definition of Universal Design, but nevertheless are part of the popular assumptions about the term.

The distinctions we wanted to make were:

The Context: Universal design has its origins in architectural and industrial design - we work in the digital realm where the constraints, design options and design methods are very different. The most important difference is that we do not need to design one-size-fits-all, the flexibility of the digital gives us the luxury and freedom to take a one-size-fits-one personalized design approach to inclusion.

The User: Universal design, despite the fact that it has the term universal in it, and counter to the intentions of the originators of the term, has become associated with disabilities and a fairly constrained categorization of disabilities. Other than the commonly quoted principles of Universal Design, much universal design guidance categorizes design advice according to constrained categories of disability. We want to stress that the individual is multi-faceted and the constraints or design needs they have may arise from a number of factors or characteristics, and they all need to be taken into account (e.g., I may be blind, but I don’t read Braille, I have some residual vision so the pictures help me navigate, also French is my second language and I’m currently juggling my kids and my job and haven’t slept all night so I’m stressed and a little bit distracted).

The Method: While the common goal is inclusion, because we are dealing with digital design our design considerations are very different from the non-digital, we can have a differently configured “entrance” for each person, in fact we can have multiple entrances for one person, each for a different context. Similarly we can have a different “handle” for each person and each context or each goal. The design constraints are very different from the domain in which Universal Design originated. While Universal Design is about creating a common design that works for everyone, we have the freedom to create a design system that can adapt, morph, or stretch to address each design need presented by each individual.

The common notions with Universal Design that we espouse and stress are:

- Designing systems so they work for people with disabilities results in systems that work better for everyone.

- Segregated, specialized design is not sustainable and does not serve the individual or society in the long run. You may ask are we not taking specialization to the extreme? Yes, in one sense we are, but it is common specialization that comes as an integrated part of the system – whether you have a disability or do not have a disability.